Donald Scott Sr., Camp William Penn (Images of America: Pennsylvania). (Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008).

|

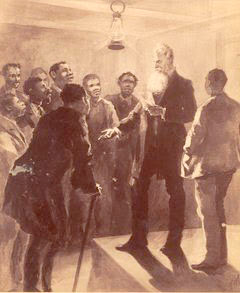

| Recruitment poster for Camp William Penn, 1863 |

I live in an historic neighborhood. My township of Cheltenham PA on the northern boundary of Philadelphia was a center of abolitionist activity in the 19th century. The area was known as Chelten Hills then. It is now divided into Elkins Park, Melrose Park (my home), and LaMott.

|

| "Roadside" home of James and Lucretia Mott |

La Mott was the site of the first and largest Union training ground for African American troops at Camp William Penn during the Civil War from 1863-1865. The land was leased to the Federal government by Edward M. Davis, who was the son-in-law of abolitionist and reformer Lucretia Mott. Lucretia and husband James retired to their son-in-law’s Chelten Hills farm in 1857 to an old farmhouse called “Roadside”. Their home was a stop on the underground railroad en route to freedom for escaped slaves. She hosted many prominent abolitionist leaders at Roadside – Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Octavius V. Catto, William Still, Robert Purvis, Sojourner Truth, William Lloyd Garrison. Even Mary Brown stayed at Roadhouse while her husband John Brown awaited trial for his raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859.

|

| AME Church of LaMott |

Chelten Hills was also home to Lucretia’s banker friend Jay Cooke

(1821-1905), who became known as the financier of the Civil War. Between 1862 and 1865 he sold $830 million in war bonds, at a commission of .375%. It was good politics and good business. He and Edward Davis were members of the Union League of Philadelphia (ULP), formed in 1862 “to discountenance and rebuke by moral and social influence all disloyalty to the Federal Government.” The ULP raised money to recruit troops for the Union, and sponsored five black regiments of US Colored Troops (USCT) at Camp William Penn. Before the Civil War, abolitionist sentiment was weak in Philadelphia. Abraham Lincoln received only 2000 votes out of 76,000 cast in the city in the 1860 election. The ULP converted Philadelphia to the Republican cause during the war. They even endorsed Radical Reconstruction after the war, including desegregating the streetcars.

Donald Scott Sr. has written two books about Camp William Penn -

Camp William Penn (Images of America: Pennsylvania), and Camp William Penn: 1863-1865 (2012). Scott is an English Professor at Community College of Philadelphia, and a Cheltenham resident and booster. He has assembled an amazing collection of 19th century photographs of the Camp and the township. I wish more historians made an effort to include illustrations. It adds interest and sells books. Old history books and fiction always had photographs or artwork. Maybe modern publishers will revive this tradition. It would create employment for illustrators and photographers. All that remains of Camp William Penn today is the restored front gate and main entrance on Sycamore Street. A neighborhood community group, Citizens for the Restoration of Historic LaMott, has made an on-and-off effort over the years to establish a museum and park commemorating the unique history of LaMott. The old 1910 LaMott fire station on Willow Avenue is the temporary home to archives and artifacts from Camp William Penn. Tours of the museum are by appointment only.

Camp William Penn served as the training ground for 11 regiments, 10,940 men, between July 1863 and July 1865. 1056 soldiers from Camp William Penn perished during the war. It is an ugly story, but many black soldiers and their white commanders were executed if they were captured in battle by Confederate troops. The burial ground for local US Colored Troop veterans of the Civil War is Butler Cemetery in Camden NJ at Ferry Avenue and Charles Street. I have not visited the site, but it appears to be incorporated into present-day Evergreen Cemetery on Google Maps.. There is also the African American Civil War Museum in Washington DC which documents the history of the US Colored Troops. I must investigate. After the War, some USCT veterans served as Buffalo Soldiers and fought in the Indian wars in the West.

After Camp William Penn was decommissioned, Edward Davis sold off lots and became the prime real estate developer of the new working-class neighborhood called Camptown. As a devout Hicksite Quaker, Davis sold to blacks and whites. To encourage development, Davis built a schoolhouse in 1878, and donated land for a community church in 1888, now the site of the AME Church of LaMott on Cheltenham Avenue. In 1885 the village received its first US post office and changed its name officially to LaMott in honor of their revered resident Lucretia Mott (1793-1880). In the late 19th century it became one of the early interracial communities in the nation. It remains so today. The latest arrivals to the township have been Asian-Americans in the last 40 years. The 2010 census reports the population was 56.6% White, 32.8% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 7.7% Asian, and 2.5% were two or more races, 3.9% of the population were of Hispanic or Latino ancestry.

|

| African American Memorial, Washington DC |

I think Lucretia Mott would be pleased. She wrote her sister in 1863, “The neighboring camp seems the absorbing interest just now. Is not this change of feeling and conduct towards this oppressed class beyond all that we could have anticipated, and marvelous in our eyes?” This from a staunch pacifist. The Civil War would finally banish chattel slavery from the US, as nonviolent efforts had failed.